Syracuse, NY – Harry Martin’s pancreatic cancer had spread quickly to his lungs and liver. Despite a heavy dose of chemotherapy, the Mattydale auto mechanic didn’t have much time left.

But the 54-year-old’s final months came with a traumatic twist: Upstate Medical University took him to court this spring for $10,700 in unpaid cancer bills. Returning from a doctor’s appointment, Martin found the state Attorney General’s Office lawsuit on his doorstep.

“The amount of stress this caused both of us is beyond words,” said his fiancée, Linda Koberna. “We couldn’t understand why they would want to sue someone who’s terminally ill.”

Medical debt often hits people like Martin the hardest: those too sick to work and too poor to pay their bills. It also afflicts the working poor, those who make too much for Medicaid but too little to afford private insurance.

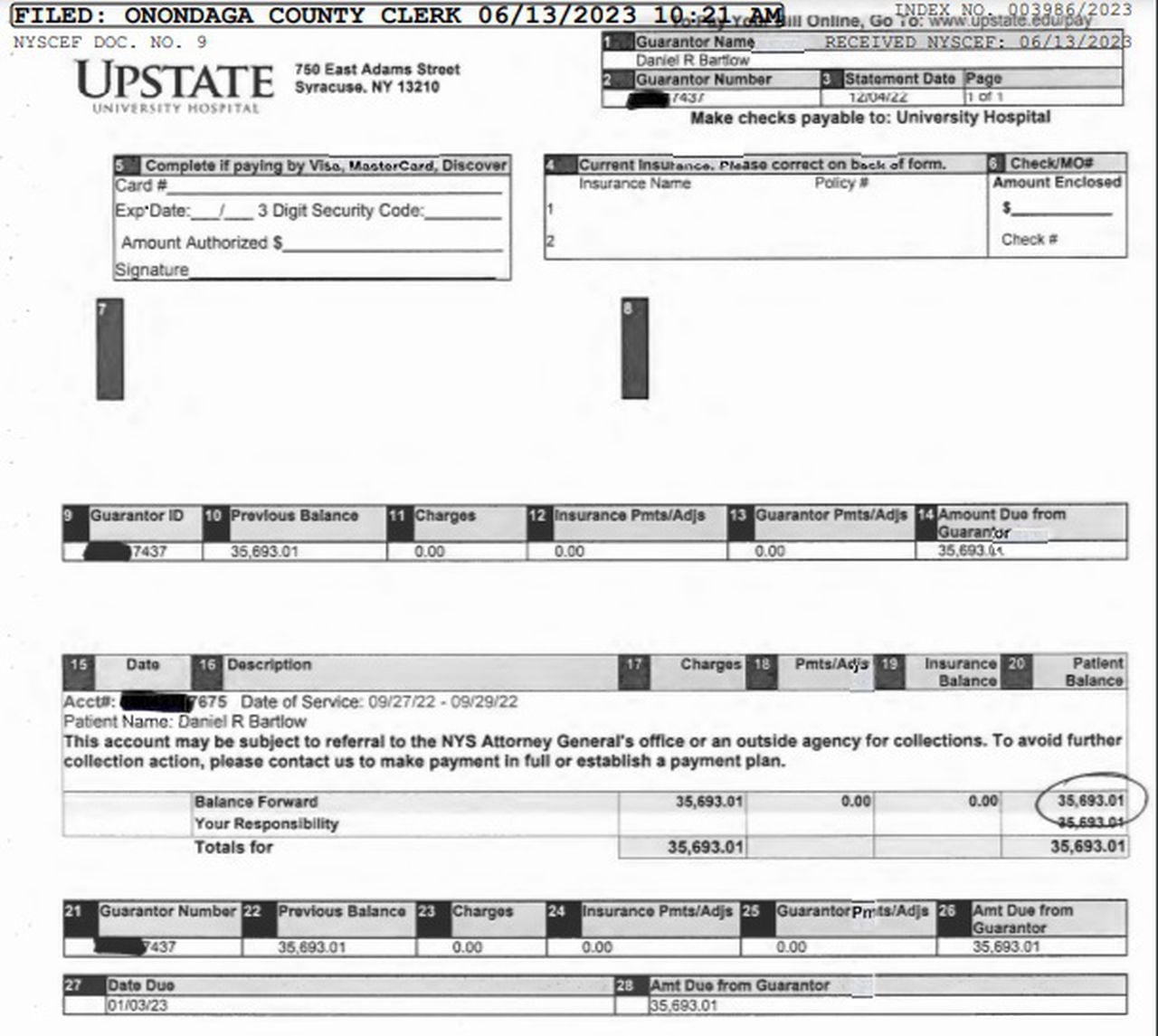

“The hospital wants to sue you. You’re the problem,” said Danny Bartlow, a dump truck driver who owes Upstate more than $35,000 after passing out while hauling rock in the Jamesville quarry. “But hey, hospital: I’m not rich. Who the hell can pay that? I sure as hell can’t.”

No one in Syracuse sues over medical debt more frequently than Upstate Medical University. The state-run University and Community General hospitals have sued more than 4,000 patients since the pandemic in 2020, while its private competitors in town haven’t sued anyone since then, court records show.

Besides Upstate, the other State University of New York hospitals, on Long Island and in Brooklyn, combine to sue thousands more patients each year, court records show.

A syracuse.com | The Post-Standard investigation shows that New York state’s public hospitals run an aggressive debt-collection lawsuit operation that adds to the pain of the patients they are charged to treat and yet produces little income in return.

Together, New York’s SUNY hospitals combined for nearly three-quarters of all medical debt lawsuits filed by hospitals statewide in 2022, according to an analysis by Community Service Society of New York, which has called for the state to stop.

Suing people for medical debt compounds the hurt for those too sick to pay, say experts and patient advocates. It’s more traumatic than other debt collection methods.

It’s also an aggressive – and rarely productive – way to collect on health bills. For every $1 Upstate refers for legal action, the hospital recoups 14 cents, according to hospital data.

The debt collection tactic leaves a public paper trail that can follow someone for two decades — if the patient lives that long.

A lawsuit that stems from a trip to the emergency room or a chronic disease can block a patient’s efforts to buy a house, get a job or even find a landlord willing to rent.

It gets worse. The state can deploy a unique power: to snatch away tax refunds from those in debt, making it harder for the working poor to get by. The state intercepts on behalf of Upstate more than $1 million a year in income tax refunds headed often to the sick and the poor, the hospital said.

With these lawsuits, Gov. Kathy Hochul, state Attorney General Letitia James and SUNY Chancellor John King are carrying out a system created by their predecessors three decades ago. Together, those now in power could sharply reduce the lawsuits that financially ruin state taxpayers and citizens.

For its part, Upstate says it only refers people for legal action after trying to reach them three times to make payment and waiting at least six months after the hospital visit.

The hospital says it has offered financial aid to needy patients who fill out the necessary forms. It provides roughly $10 million in charity care each year, the hospital said. Upstate also eats the cost of nearly $40 million a year in “bad debt,” or care that has never been paid for.

Upstate provided $45,027 in charity care to Martin, the cancer victim, but that wasn’t enough to cover the costs. They hounded him for the remaining $10,700.

But he was too sick to work and didn’t have enough to pay the bill, his fiancée said. A paperwork snafu had left him without health insurance after losing his job, she said. He lived off Social Security income in his final months.

Martin never bought something he couldn’t pay for, his fiancée said. He shunned credit cards. Even in his last days in September, the debt worried him, Koberna said.

“That’s how he was,” his fiancée said. “He always paid his bills on time.”

Upstate’s lawsuit machine

Other hospitals across New York and the nation are curbing or ending medical debt lawsuits, as they find the tactic makes little financial sense.

Syracuse’s two private hospitals, St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center and Crouse Hospital, haven’t sued anyone in nearly three years. The state’s largest healthcare system, Northwell Health, stopped suing people altogether during the pandemic. So have the nation’s largest two for-profit healthcare systems. New Mexico has outlawed medical debt lawsuits altogether for poor residents.

Advocates say ending lawsuits in New York could bring some relief to thousands of people each year. As it stands, Hochul and others already are rewriting state law in other ways to ease the burden of medical debts.

Instead, New York’s public hospitals, including Upstate, routinely sue their patients.

Upstate University Hospital includes its own state attorney general's office, which churns out more than a thousand debt lawsuits each year against patients. Michael Greenlar | mgreenlar@syr

Each workday, on average, Upstate refers six overdue bills to the state’s Attorney General’s Office. State lawyers who work inside the hospital churn those referrals into lawsuits. Hundreds each year are for $2,500 to $5,000, often a single trip to the emergency room, according to a syracuse.com analysis. The most typical debt is less than $9,000.

State officials from Upstate and the Attorney General’s Office say they have no choice. They point to a 30-year-old directive from Gov. George Pataki’s administration that tells hospitals like Upstate to refer debt to the state’s lawyer, the attorney general.

The current directive, last updated in 2017, applies to debts of $2,500 or more. This fall, Upstate sued one East Syracuse patient for $2,501.

Hochul has the authority to lift the budget directive today, freeing the SUNY system and attorney general’s office of what they say is an obligation to sue patients.

Hochul’s office did not respond to several requests for comment for this story.

Syracuse.com contacted more than three dozen people facing lawsuits from Upstate over medical debt. Few people were willing to talk about what to some is frustrating, to others embarrassing.

Others shared their stories.

‘I pay what I can’

David Smith, a tow truck driver from West Monroe, Oswego County, faces a $11,556 lawsuit from Upstate Medical University.Douglass Dowty

David Smith, 53, a tow truck driver, has lost one leg to diabetes. He faces a $11,556 lawsuit from Upstate.

“It’s been a nightmare,” Smith said.

The West Monroe resident has been in and out of the hospital in the past seven years, making it harder and harder to pay his accumulating medical bills. He’s now taking jobs at all times of the night, including a recent trip into Syracuse to haul away a car at 1 a.m., he said.

“I gotta work,” Smith said. “Nobody’s gonna pay the bills for me.”

As a small business owner, Smith doesn’t get health insurance. He survives on partial Medicare coverage he received after a car crash decades ago, he said.

That doesn’t come close to paying for his $30 a week in insulin or hundreds more a month in patches and treatments, Smith said.

Smith estimated he’s paid about $10,000 to Upstate, but knows he owes tens of thousands more. He said that the hospital determined he earns too much to get more financial aid. Smith said he tried paying $200 a month on a repayment plan.

But he couldn’t keep up and the hospital sued him again.

“I don’t care,” he said. “They probably won’t get it.”

Making things worse, Smith is now dealing with an infection in his remaining leg. And his prosthetic leg needs to be replaced again, too. Still, Smith dreams of a day he works enough to pay off his debt.

“If this infection goes away, I’m going to work even more,” he said. “I pay what I can and that’s it. The hell with it.”

No one chooses a medical emergency

Medical debt isn’t like other debt. It’s not chosen, like a fancy car or a vacation home.

“We have an ability to choose most debt,” said Assemblywoman Amy Paulin, D-Scarsdale, who chairs the health committee. “We do not have an ability to choose a medical emergency.”

That’s why Paulin sponsored a bill this September that would forbid SUNY hospitals from suing over medical debt. She says the governor could also end the practice by simply revising the budget rule that automates the lawsuits.

Ursula Rozum, a Syracuse activist who works for the reform group Citizen Action of New York, said these lawsuits almost always prey upon people who simply don’t have the money.

“There might be someone out there who doesn’t want to pay their hospital bill who might need to be sued,” she said. “But the vast majority of people are working-class people who just can’t afford it.”

Ursula Rozum, of Syracuse, who now leads health initiatives for Citizen Action of New York, says New York and Upstate are suing mostly "working-class people who just can’t afford it.”Michelle Gabel | The Post-Standard

Those who can’t settle a lawsuit can end up owing a court judgment, which is worse than contending with a private debt collector, said Elisabeth Benjamin, vice president for health initiatives at the Community Service Society.

While a debt collector can pursue someone for seven years, a court judgment can be enforced for 20 years. Judgments must be paid off before someone can obtain a mortgage to buy a house. It’s also a public record typically used by landlords to make rental decisions and employers to screen job candidates.

But this is perhaps the most impactful part of a judgment: It allows the state to intercept the patient’s tax refunds to pay the debt.

More than $1 million a year is seized for Upstate from people with medical debt, the hospital said. It’s a mechanism only available to state hospitals. Private institutions can’t do that.

It’s what happened to Jusdene Kilbourn, 26, of Syracuse, who lost her father’s union health insurance in 2019 and wasn’t yet enrolled in Medicaid, she said.

The Near West Side resident did what many uninsured patients do: She went to the emergency room when health problems arose.

Upstate sued her for $2,566 after a one-time trip to Community General’s ER, court records show. When she was unable to pay, New York started taking out her entire state refund, roughly $500 a year, she said.

Given her eligibility for Medicaid, it’s unclear why Kilbourn wasn’t offered charity care as a low-income resident. She’s since been enrolled in a health insurance program for the poor.

‘I don’t know what to do’

Bartlow, of South Onondaga, is the dump truck operator who owes Upstate $35,693 after passing out in the quarry. He was working for a small contractor in September 2022 when he suddenly became lightheaded and fainted.

He spent two days at Upstate getting CT scans and screenings. Doctors said it could be epilepsy, he said. That’s a pre-existing condition not covered by his employer’s worker’s comp.

Bartlow disagreed, but still got sued for the full hospital bill. With the help of a lawyer, he demanded a detailed copy of his hospital bill.

Upstate responded in court with a one-page bill with no explanation of what services he was being charged for. It included only his name, the dates of service and a demand for payment of $35,693.

This is the hospital bill filed as proof of medical debt against Danny Bartlow, of South Onondaga.Court record

Before his fainting episode, Bartlow said, he’d turned down the high-deductible health insurance through his small company, instead taking his full $26.50-an-hour salary and hoping nothing went wrong.

The health insurance he turned down cost $200 a week and required him to pay the first $1,500, he said. After reaching the deductible, he would have still had to pay 40% of the remaining bills, Bartlow said.

“I couldn’t afford to get sick,” he said.

After his hospital stay, Bartlow said, he went on Medicaid for a few months before finding a new job with full health insurance. But Upstate’s lawsuit still follows him.

“I don’t know what to do,” he said. “It’s going to affect my credit and put me behind as far as bills go. I wasn’t making a lot of money to begin with.”

Some fixes under way

Ending lawsuits won’t end medical debt: It’s an entrenched part of our nation’s healthcare system. The way our nation provides and pays for basic medical care shares in the blame for these lawsuits.

Upstate, like nearly every other hospital, refers patients to private debt collectors if they owe less than $2,500. Anything above that amount triggers a lawsuit.

In the past five years, Upstate sent 110,054 patients owing $43 million to debt collectors, the hospital said. Its private competitors, St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center and Crouse Hospital, go after debt in the same way, court records show.

A recent study claimed that 25% of Syracuse adults – roughly 28,000 people — are saddled with medical debt in collections. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that more than half of U.S. adults had gone into debt because of medical or dental bills in the past five years.

In recent years, New York has made strides in reducing the impact of medical debt on its residents. It has outlawed garnishing wages or placing liens on primary residences to collect medical debt.

On Wednesday, the governor signed a law that bans medical debt from lowering consumer credit scores. That’s a big help to people burdened with medical debt – as long as they don’t get sued.

For years, people with unpaid medical bills have seen their credit scores plummet, much like those who don’t pay their credit cards. A low credit score can have a similar, if less profound, impact as a lawsuit: ruining your chances of getting a car loan, finding an apartment or landing a job.

The new credit reporting ban will help people like Yvonne Griffin, 47, of Syracuse.

Her son’s decade-old bicycle accident is the biggest drag on her credit score, which at 520 is too low to get credit of any kind, she said. She’s been living with a family member after losing her last apartment this summer.

“It’s hard to find housing, especially with that credit score,” Griffin said.

But even with her medical debt removed from credit reports, it’s still there for anyone to see. That’s because Upstate sued over her son’s care in 2014, eventually getting a default judgment that will remain on Griffin’s public court record. The state is intercepting her tax refunds for repayment, she said.

Yvonne Griffin, of Syracuse, is saddled with a court judgment over treatment for her son, who was injured in a bicycle accident. Scott Schild | sschild@syracuse.com

What more can be done?

All public and non-profit hospitals are obligated to provide free or reduced-price care to those who cannot afford it. That’s one of the main reasons they avoid paying taxes.

Still, many people sued for medical debt qualify for hospital financial aid but either slip through the cracks or are turned down, advocates say.

The reasons for that are not clear. But money meant to compensate hospitals for charity care is not providing enough incentive to make sure all qualified patients get aid, Benjamin said.

Advocates like Rozum and Benjamin are rallying around a new state bill, called the Ounce of Prevention, which would set up uniform financial aid rules for all hospitals in the state.

The bill, sponsored by Paulin in the Assembly, would force hospitals to do their own research to check if uninsured patients are eligible for financial assistance. Right now, hospitals often leave it up to the patient to prove they are eligible.

It also would increase the income limits to allow more uninsured people to qualify for financial aid. For example, hospital care would be virtually free to anyone under 200% of the poverty line, up from 100% rule now. That would double the income limits for a family of four from $30,000 to $60,000 a year.

These provisions would most benefit the working poor: those making too much for Medicaid but too little for some private insurance.

A dying wish

That comes too late for Martin, the cancer patient who spent his last days fretting over Upstate’s lawsuit against him.

Martin’s debt came from a single month of cancer treatment, from Aug. 2 to 31, 2022, court records show. That was the gap between losing his job and getting signed up for Medicaid, Koberna said.

Koberna first spoke to a reporter by phone from Martin’s bedside in early September as he tossed uncomfortably while propped up by a cocktail of pain medications. She said she was honoring one of Martin’s dying wishes by speaking out against Upstate’s treatment of patients in debt.

“The last thing they need is the burden of a lawsuit,” Koberna said.

Martin died on Sept. 10.

Three weeks after his death, the state sent Martin another bill for $4,600 that wasn’t included in the lawsuit, Koberna said.

She wrote them back with a simple message:

“He’s not here anymore. You’re not getting it.”

Staff writer Douglass Dowty can be reached at ddowty@syracuse.com or (315) 470-6070.